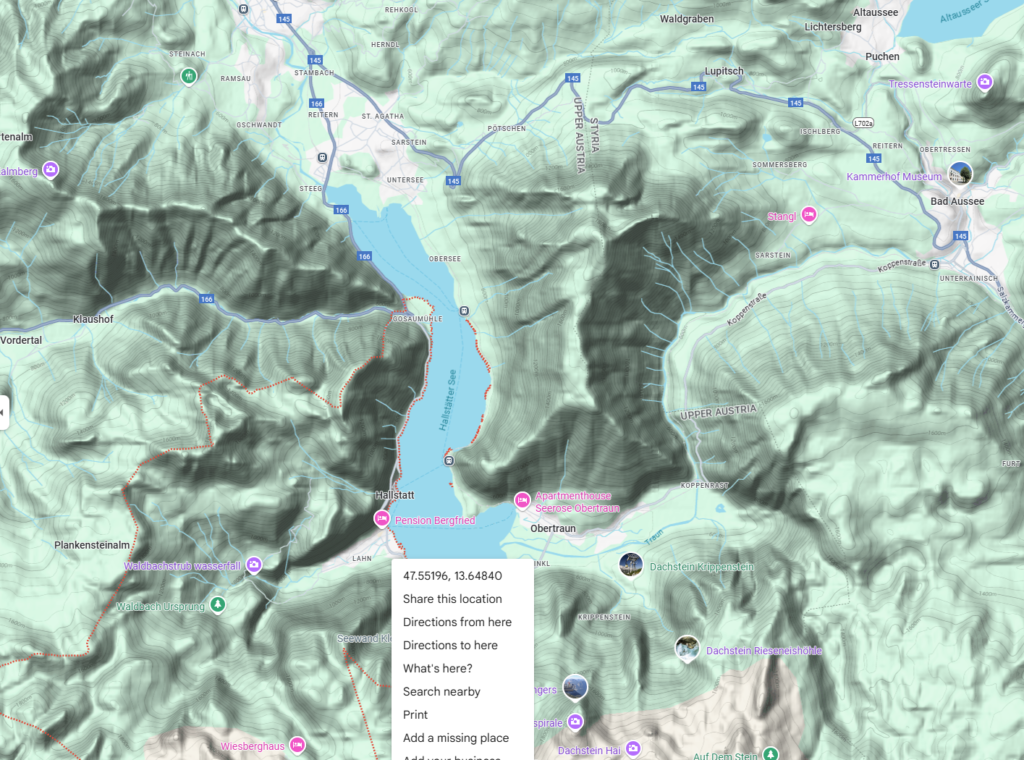

There is something timeless and universal about our connection to mountains. Whether it’s the jagged teeth of the Himalayas or the gentle curves of the Alps, the sight of these natural wonders captures our imagination and fuels our sense of adventure. With the advance of satellite technology, especially the initiatives from the European Space Agency (ESA), we now have the unprecedented ability to capture the Earth in intricate detail. The Copernicus programme, the EU’s flagship Earth observation mission, has democratized access to this satellite data like never before. It’s this incredible resource that made the PeakPrinter project possible: a tool that allows anyone to generate a precise STL file of their favorite mountain, hill, or valley on Earth and bring it to life through a 3D printer. See an example of the famous village of Hallstadt in the Austrian Alps.

The PeakPrinter project was born out of a simple yet powerful idea: what if you could hold your favorite landscape in the palm of your hand? Whether you’re a mountaineer looking to memorialize your first summit, a geography teacher aiming to provide tactile learning tools for your students, or simply a 3D printing enthusiast fascinated by the world, PeakPrinter delivers on that dream. The concept is powered by the freely accessible Copernicus Digital Elevation Model (DEM), specifically the 30-meter resolution global data hosted on AWS under an open license. This kind of dataset, once restricted to government and research use, is now just a few lines of Python code away from any curious mind. Thanks to the EU’s commitment to open data, geographical and topographical exploration has become radically more inclusive.

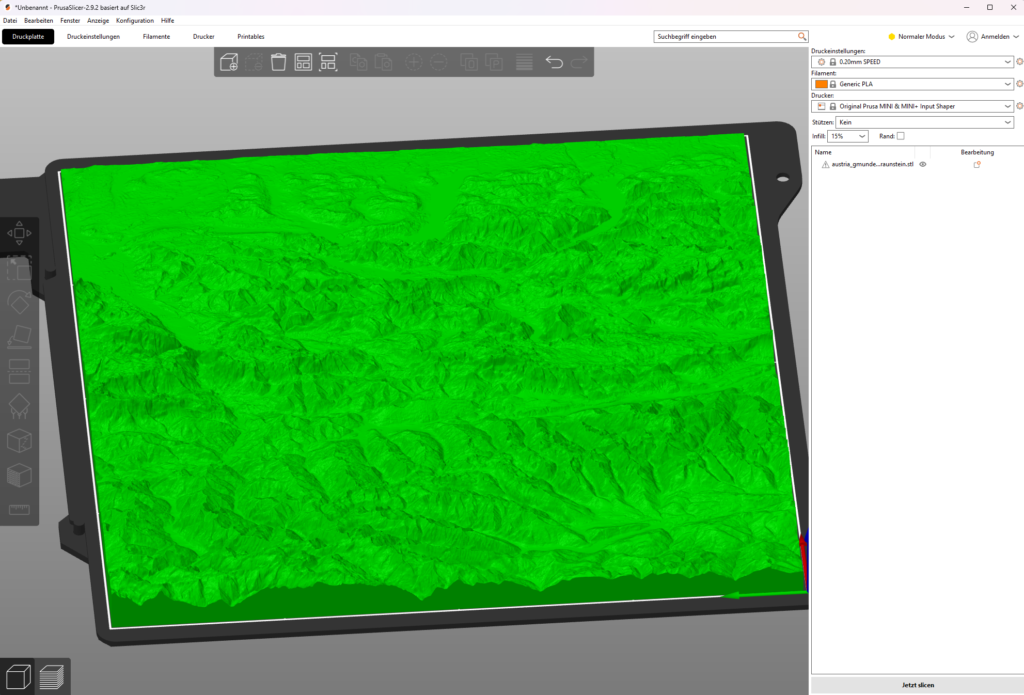

Using PeakPrinter is remarkably straightforward. Users provide the latitude and longitude of any location on Earth—be it Mount Everest, the Austrian Traunstein, or a hidden valley in the Andes—and the tool fetches the corresponding DEM tile from the Copernicus S3 bucket. With that data in hand, the software then converts the raster elevation data into a 3D mesh, scales it appropriately, and outputs a high-fidelity STL file ready for slicing and printing. The end result is a beautiful, tangible terrain model that faithfully reflects the real world, scaled down to your printer’s build plate. This translation from orbital data to physical object is a modern alchemy, and it’s made possible only through the ESA’s visionary data initiatives.

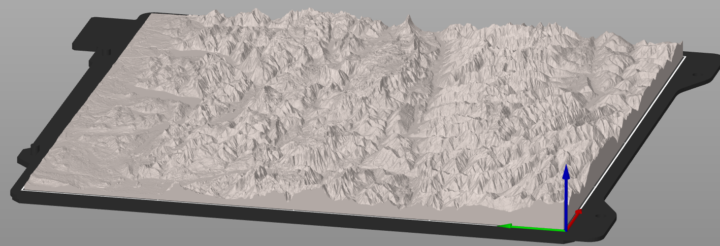

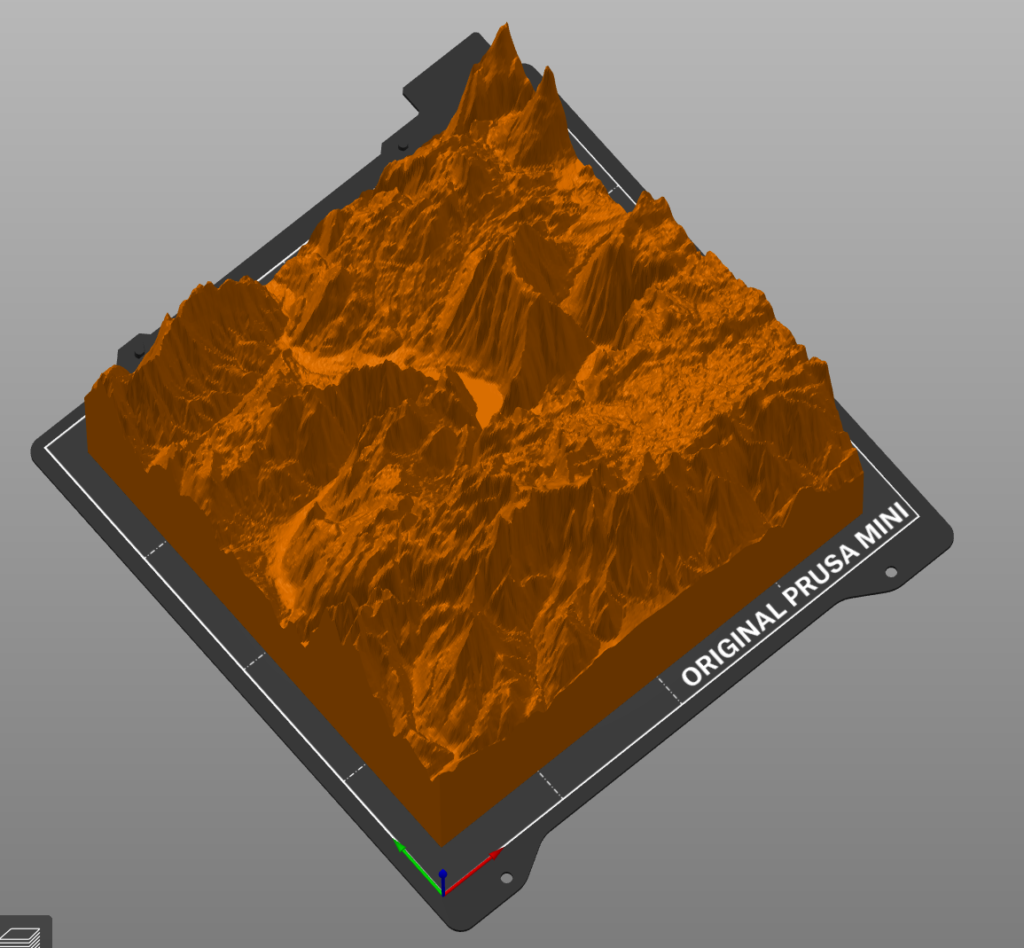

See below the area around the famous village of Hallstadt in the Austrian alps, extracted from ESA satelite data, transformed into a 3D printable STL file.

Behind the scenes, PeakPrinter leverages powerful open-source tools such as Rasterio for reading GeoTIFFs, NumPy for data manipulation, and numpy-stl for generating 3D meshes. The code processes the DEM data by sampling elevation values, constructing vertices, and generating triangles to form a mesh. Elevation can be exaggerated to enhance visual impact, especially for flatter terrains. A base can be added for 3D printability, ensuring the model sits flat on a surface. Despite the complexity of satellite imaging and 3D geometry, the PeakPrinter interface abstracts away the technical difficulties, offering a smooth experience for users of all backgrounds. It’s a fusion of geospatial science and maker creativity, enabled entirely by public infrastructure.

One cannot overstate the importance of the Copernicus programme in this context. By releasing high-resolution elevation data under a fully open-access model, the European Union and ESA have opened the door to countless educational, artistic, and scientific applications. No paywalls, no institutional gatekeeping—just raw, accurate, and beautifully maintained geospatial data. In an age when so much digital information is locked behind subscriptions and API keys, the Copernicus initiative stands as a shining example of what publicly funded science can achieve. The datasets are precise, up-to-date, and well-documented. Without them, a project like PeakPrinter would either be impossible or prohibitively expensive for everyday users.

But this project is not just about printing pretty mountains. It’s about making the abstract real. It’s about empowering people to interact with Earth science in a way that’s deeply personal and highly accessible. Want to study the effects of glacial erosion in the Alps? Print it. Want to teach students how valleys are shaped over millennia? Print it. Want to commemorate your trip to the Grand Canyon? Print it. The ability to take real-world topography and manifest it into a physical object enhances understanding and appreciation in a way that maps and screens simply cannot.

Moreover, PeakPrinter showcases the incredible potential of combining open satellite data with consumer-level 3D printing. As both domains mature, we can expect to see even more sophisticated tools emerge—tools that let you manipulate terrains, simulate erosion, overlay historical changes, or even generate printable models of Mars and the Moon. For now, though, Earth is more than enough, and with Copernicus DEM as a foundation, the possibilities are vast. Enthusiasts are already sharing prints on social media, exchanging settings, scaling techniques, and showcasing time-lapse videos of their printers carving out the Dolomites layer by layer. The community around terrain printing is vibrant and growing, and much of its momentum is thanks to what PeakPrinter enables.

In many ways, PeakPrinter is a love letter to both the physical world and the digital infrastructure that allows us to understand it. It celebrates the spirit of exploration and the joy of creation, turning gigabytes of satellite imagery into something you can touch, share, and admire. It lowers the barrier between data and imagination, between the satellite and the studio. And most importantly, it reminds us that when public institutions like the European Union and ESA make knowledge freely available, innovation follows.

As the project continues to grow, there are plans to add GUI support, integrate automatic tile stitching for larger areas, and potentially launch a web interface for instant model generation. But at its heart, PeakPrinter will always remain a celebration of the Earth’s landscapes and the shared resources that allow us to experience them anew. What once required millions of euros in satellite infrastructure and exclusive software licenses can now be done in an afternoon with an internet connection and a passion for discovery.

So if you’ve ever dreamed of holding your favorite peak, now you can. Thanks to the visionary work of the ESA, the generosity of the Copernicus open data policy, and the power of everyday tools, the mountains are no longer out of reach. They’re ready to be printed.

Read about other life-saving 3D prints in my eBook ‘3D Print Life Hacks’.